WHY THE 'SCHEDULER' IS MORE THAN A REMINDER

- Shellie A.B. Christensen, Ph.D.

- Dec 10, 2017

- 4 min read

Do we really know how pain changes? This is why tracking pain is important. Many of us are aware that feeling pain when we have an injury such as a small cut or bruise is normal. In fact, its quite healthy to do. We also know pain can occur with more serious injuries such as ankle sprains. But what about the millions of cases of unexplained neck or back pain? Neck and back pain are so common that it lead one to believe that it is normal too. Yet our rationale brain knows otherwise.

How does pain change?

Often the onset of unexplained (idiopathic) neck or back pain does not involve one single memorable event. For some the pain will resolve after a few weeks. In many cases the pain continues for years, often as short episodes re-occurring without warning. Unfortunately, little it known about what happens in between pain onset and resolve or between re-occurring episodes.

In recent article ‘What have we learned from ten years of trajectory research in low back pain?’ appearing in BMC Musculoskeletal Disorders, Kongsted and colleagues (2017) reviewed a number of studies that tracked pain intensity in individuals with low back pain. The review examined 10 cohorts and assessed the results from data collected from studies dating back to 2006.

A proposed terminology of how pain changes over the long-term were as follows:

Persistent pain

Fluctuating pain

Episodic pain (including a single episode of pain)

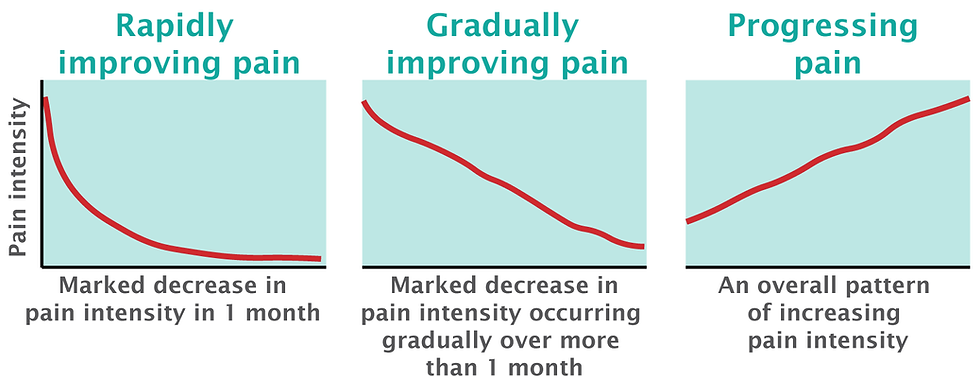

Kongsted and colleagues (2017) suggested three terms for describing how pain changes and are simply portrayed in Figure 1:

From the review, the most frequent pain tracking assessment was made fortnightly, that is once every two weeks. Kent and colleagues (2012) showed pain tracking these large time intervals does not produce simple smooth lines like those in Figure 1.

Infrequent ratings are likely due to technical barriers of collecting daily pain ratings.

Indeed technical barriers may be why we lack information on pain map patterns. This may also explain why pain is rarely monitored after onset and to the extent necessary to capture vital information about how pain changes. This is unfortunate given that the understanding of how pain transitions from acute to chronic remains elusive. So where does that leave us?

Look at the scheduler

We can begin by finding out what happens in between by asking patients to tell us. As clinicians and researchers, we can start by tracking the intensity, area, locations, and pain type. We can ask patients to report this information daily, weekly, or monthly.

We can track pain digitally using Navigate Pain and scheduled patient reminders.

From a clinical perspective, each patient is unique, and common sense tells us that if we want to make any predictions we must look to the patient’s pain history. A patient's history may include yesterday but it could also include last month or one year ago.

But how can we look back if their is no proper documentation? How can we truly listen if we don’t empower our patients with tools to tell us what is happening after and between consultations?

The Navigate Pain ‘Scheduler’ lets patient tell us what’ is happening when we are not there.

Navigate Pain has a custom calendar feature known as the Scheduler. By choosing a start and end date it is possible to capture what is happening today, tomorrow and the next day. For example a patient can enter their information about pain intensity, area and location up to three times per day over several weeks or months.

Let the pain map emerge

The Scheduler prompts patients to enter their information on their phone, computer or tablet, which can improve reporting compliance. This level of detail captures the incremental and daily changes. As multiple entries builds it becomes possible to see how the pain is changing. Even better, the pain charts serve as documentation. If continued more specific patterns may emerge. By using the Navigate Pain timeline viewer, another powerful feature, the pain maps can viewed in series like a short-video.

We can collect a series of pain charts using the Scheduler. The series of pain charts can inform us about the trajectory of the pain reports. The pain report includes intensity, pain type in relation to pain maps of the body. The location of pain may shift or spread.

Painful areas may expand into other body regions or suddenly appear distant to the original pain location. Thus, a spread of pain is less subjective than the pain intensity score itself. As simply said by a good colleague and pain specialist:

'Pain is either present or absent and body map documents that - there is no in between.'

Scientists and the scheduler

To date, we know that chronic pain (i.e. pain lasting longer than 3 months) associates changes in the central nervous system (CNS) known as central sensitization. Today, the Navigate Pain Scheduler is helping scientists answer additional deep questions such as how and why does pain persists. A persistent question within the scientific community (Yes, pun intended).

The Scheduler is a core feature of the Navigate Pain software. Scheduling is a powerful tool and when used strategically and can serve scientific, clinical and patient goals. In a recent online study, Navigate Pain facilitated data collection from patients over a six month period (Galve Villa et al., 2020). This study showed patients with chronic pain fluctuate often and case analyses revealed pain intensity did not reflect changes or spread of pain and other pain qualities.

We will only begin to see and learn more by observing and listening to what patients have to tell us. Can it be any other way?

References

Alice Kongsted, Peter Kent, Iben Axen, Aron S. Downie , and Kate M. Dunn. What have we learned from ten years of trajectory research in low back pain? BMC Musculoskeletal Disorders. 2016: 17:220.

Kent P, Kongsted A. Identifying clinical course patterns in SMS data using cluster analysis. Chiropr Man Therap. 2012;20(1):20.

Galve Villa M, S Palsson T, Cid Royo A, R Bjarkam C, Boudreau SA. Digital Pain Mapping and Tracking in Patients With Chronic Pain: Longitudinal Study. J Med Internet Res 2020;22(10):e21475 DOI: 10.2196/21475

Comments